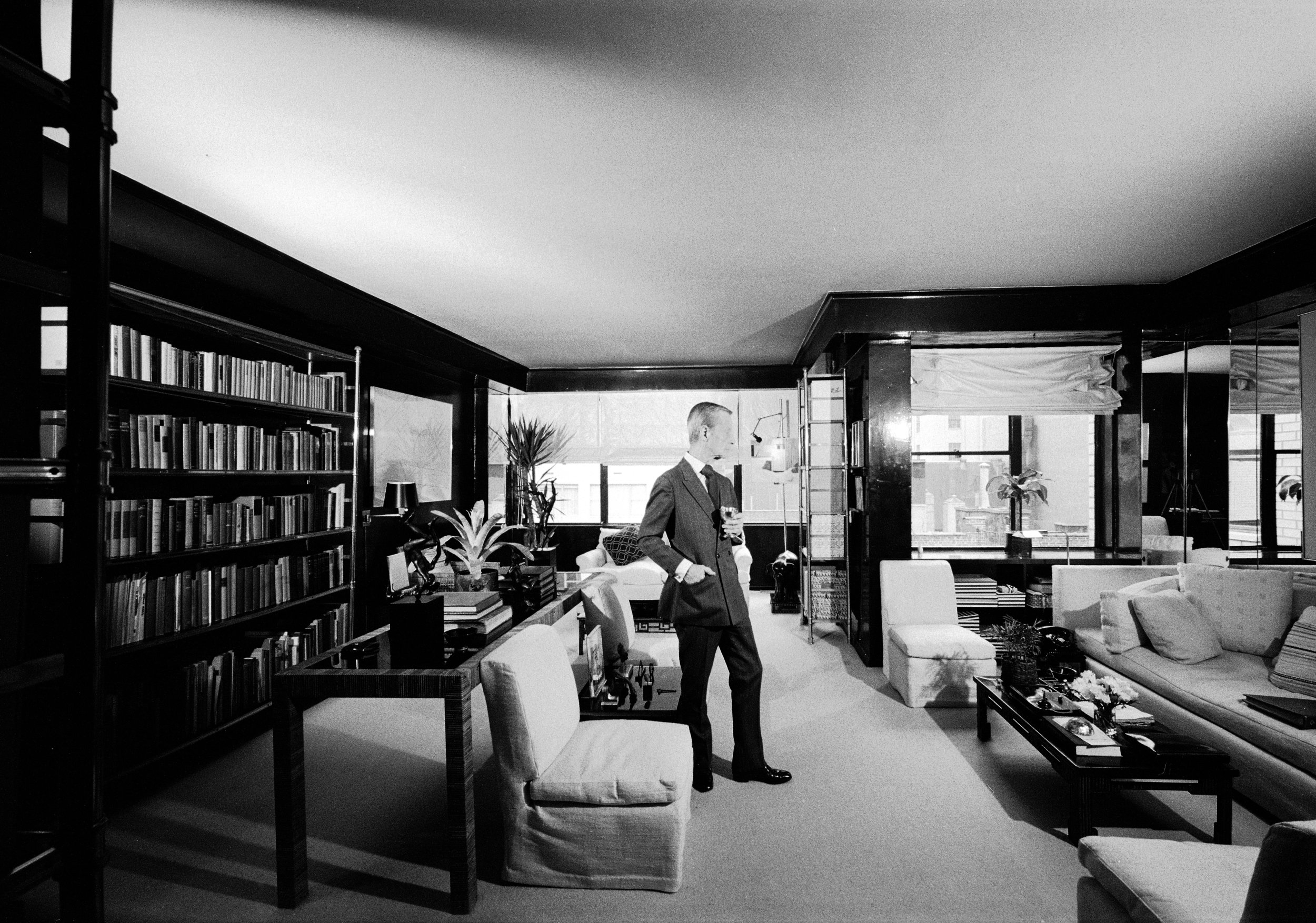

Interior decorator Billy Baldwin in his self designed apartment, circa 1974

(Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Most design aficionados have their “heroes”—figures they look to for inspiration. The same holds true for interior design professionals, who regularly reinterpret the greats of the past for their own clients. At McBournie Richards, the design books behind our desks are well-worn, but none more so than those on Billy Baldwin—a man who disliked the word “designer” and preferred to be called a decorator.

William Williar Baldwin, Jr. was born May 30, 1903, in Baltimore, Maryland. His father owned a successful insurance agency, and his mother descended from one of Maryland’s wealthiest families, with roots in colonial Connecticut. Baldwin grew up in a fashionable neighborhood, surrounded by the trappings of refined taste.

When Billy was ten, he encountered the work of Henri Matisse for the first time in the Baltimore home of Etta and Dr. Claribel Cone—sisters, renowned art collectors, and friends of Gertrude Stein. He later credited Matisse with “emancipating us from Victorian color prejudices,” embracing his palette of bold, modern hues. Just as importantly, that childhood visit awakened in him a fascination with the way art, objects, and interiors could shape an environment—a love of design that would guide the rest of his life.

Equally formative was his father’s devotion to style. Twice a year, Baldwin accompanied him to fittings with Savile Row tailors visiting Baltimore from London. Custom suits, jackets, and shoes instilled in him a reverence for detail and quality—an elegance he would later carry into his interiors. His sartorial polish eventually earned him a place in the International Best-Dressed List Hall of Fame.

Baldwin’s schooling was less steady. He attended the Gilman School for Boys in Baltimore, except for one year at the Westminster School in Connecticut. His father, concerned that Billy was spending too much time with his mother, sent him away that year in hopes of toughening him. Afterward, Baldwin briefly enrolled at Princeton, but poor grades led to his dismissal. He returned to Baltimore, working first at his father’s insurance firm and then at a local newspaper, before his mother arranged an apprenticeship with her decorator, C. J. Benson. Under Benson, Baldwin learned the fundamentals of the decorating business: working with drapery and upholstery shops, managing installations, and cultivating clients.

After several years under Benson’s guidance, Baldwin began to make a name for himself in Baltimore. His eye for color, proportion, and comfort distinguished his work from the more traditional interiors of the day, and word of his talent began to spread. In 1930, legendary New York decorator Ruby Ross Wood visited one of Baldwin’s early houses and declared it “a beacon of light in the boredom of the houses around it.” She soon invited him to join her practice, which he did in 1935. For the next fifteen years, Baldwin absorbed her wisdom, which he later distilled into a mantra: “the importance of the personal, of the comfortable, and of the new.” After Wood’s death in 1950, he stayed on to complete outstanding commissions before striking out on his own.

In 1952, Baldwin and Edward Martin, his former colleague at Wood’s firm, opened Baldwin Interiors, later renamed Baldwin & Martin, Inc. Their breakthrough came with a project for dress designer Mollie Parnis, published in Vogue. From there, business flourished. By the 1960s, Baldwin’s client list included many of America’s most influential tastemakers—Nan Kempner, Paul and Bunny Mellon, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Diana Vreeland, William S. and Babe Paley—along with elite establishments such as Kenneth’s salon and the Round Hill Club in Greenwich.

Cole Porter's Waldorf Towers apartment, with its floor to ceiling Directoire-inspired tubular brass bookcases placed against lacquered tortoiseshell-vinyl walls.

Diana Vreeland requested that Baldwin transform her drawing room into a “garden in hell.”

The Baldwin-designed Manhattan home of Mr. and Mrs. Lee Eastman.

Baldwin’s style was both classic and modern. He generally disdained the ornate in favor of a pared-down, cleaner look that came to be recognized as distinctly American. Hallmarks of a Baldwin interior included cotton—he called it “his life,” though he also favored blue denim—along with white plaster lamps, pattern-on-pattern, dark walls, matchstick blinds, swing-arm brass lamps, armless slipper chairs, corner banquettes, wicker-wrapped Parsons tables, and shelves filled with books. His pet aversions were equally strong: satin and damask, ostentation of any kind, clutter, fake fireplaces, and false books.

Billy Baldwin designed this patterned black-and-white textile, Arbre de Matisse Reverse (formerly called "Foliage"), in 1965 with and for client Woodson Taulbee. The inspiration came from the black ink tree in the background of the Matisse painting above the sofa.

For Baldwin, the ultimate luxury was comfort. “First and foremost, furniture must be comfortable,” he declared. His taste in furniture was eclectic, and he often incorporated pieces clients already owned, so long as they met his non-negotiable standard: quality. He routinely favored contemporary pieces over reproductions, and when the project called for it, he designed his own. Among his most iconic contributions were the Directoire-inspired brass étagère created for Cole Porter, the cane-wrapped chair adapted from a Jean-Michel Frank design and handcrafted by Bielecky Brothers, the “X” bench, and above all, the Baldwin slipper chair. That now-legendary armless chair evolved from Ruby Ross Wood’s mini-Lawson sofa; Baldwin refined and shrank the form into a versatile perch, perfect for a cocktail party or an evening in front of the television.

In the early 1960s, Baldwin faced a deeply personal setback. Errors in his accounting led to an indictment for federal income tax evasion. To keep him out of prison, a loyal client and friend paid his fines. The government garnished his income for the remainder of his life, forcing him to sell his home and move into a modest studio on East 61st Street. Ironically, this studio became one of his most photographed projects.

In 1971, Baldwin made his assistant Arthur Smith a partner, and the firm became Baldwin, Martin & Smith. Just over two years later, at the age of seventy, he retired, selling the company to Smith, who promptly renamed it Arthur E. Smith, Inc.

Baldwin remained in Manhattan for several years after retirement but ultimately found it too expensive to live there without working. He chose instead to return to Nantucket, where he had first summered as a boy and continued to visit throughout his life. The move presented challenges: the island had few year-round rentals, and Baldwin lacked the funds to buy a home. Two close friends, Way Bandy and Michael Gardine, converted a small structure behind their house into a two-room guest cottage for him. Baldwin claimed he liked it better than anywhere he had lived since his family home in Baltimore.

By then, however, he was suffering from advanced emphysema, a condition aggravated by Nantucket’s damp winters. Though he was able to escape to warmer climates for a time, his health declined steadily. On November 25, 1983, Billy Baldwin passed away. True to his wishes, there was no memorial service, and his ashes were scattered on a Nantucket beach.

Billy Baldwin’s interiors embodied a philosophy that still resonates today: comfort as the ultimate luxury, restraint over ostentation, and a belief that homes should be as individual as the people who live in them. He insisted, “There must be sympathy, congeniality, and mutual admiration between you, your architect, and your decorator. There is a lot of hard work ahead, and it must be done with joy and smiles, not scowls.”

He rejected fleeting fads, noting, “Trends is a word I hate. The inventions of manufacturers, trends are used to promote business. Trends are the death knell of the personal stamp in decorating. If I found that something I was doing had become a trend, I would run from it like the plague.” For Baldwin, the true constants were comfort, proportion, and quality. “The first step in decorating and furnishing a room or a house,” he advised, “is having an up-to-date floor plan.”

Baldwin’s pared-down elegance balanced classic and modern sensibilities. “In the end, decorating is all about color. Think about colored flowers on bright white cotton and, in the same room, right next to this celebration of color, is more color—fresh flowers, lots of them.” He also believed deeply in the role of personal touches: “I have always contended that books are the best decoration of all. Certainly there is not a room in the house where they do not fit.”

It’s no wonder his books are the most dog-eared in our office. They remind us daily that the best interiors are not only stylish and modern but also deeply personal, comfortable, and enduring. Baldwin’s voice—direct, witty, and uncompromising—remains a touchstone, inspiring us to balance tradition with fresh perspective, just as he did.

Baldwin’s own New York City apartment.

To learn more about Billy Baldwin:

"Billy Baldwin, The Great American Decorator", by Adam Lewis

"Billy Baldwin Decorates", by Billy Baldwin

"Billy Baldwin Remembers", by Billy Baldwin

"Billy Baldwin, an Autobiography", by Michael Gardine